![]()

DRCongo) Epics of the Forest Heroes: Oral Traditions of the Songola People (français ci-dessous)

2023/09/08

Corrigendum (9/10/2023):

nsáku (African olive, olivier africain) --> nsákú (African pear, Dacryodes edulis)

A manuscript to be published in Japanese in:

Takeuchi, Shin’ichi & Daiji Kimura (eds.) (2024). Fifty Chapters to Know the Democratic Republic of Congo, Akashi Shoten, Tokyo.

Epics of the Forest Heroes: Oral Traditions of the Songola People (DRC)

ANKEI Yuji (Institute for Biocultural Diversity, Japan)

When I lived in a village in the forest along the Lualaba River, 2,700 kilometers up the Congo River from its mouth, I used to enjoy listening to various oral traditions at night, such as folk tales and riddles in which animals were the main characters. I heard a long story for the first time in 1983, during my third stay. The story took 45 minutes to tell. The narrator was Mr. Bitonde Kaombi, then in his thirties, born and raised in Kindu, Maniema Province. The story, told in the Binja dialect of Songola, his mother tongue, was a high art form with a truly lively theatrical presentation and numerous songs that he sang with his audience.

I tried to transcribe the tape recordings, bit by bit, using the descriptions in the Congolese dialect of Swahili as a guide. The synopsis of the heroic epic of the Songola, which has never been introduced to the world, goes as follows.

Once upon a time, a village chief married ten wives. He declared that he only wanted the girls because a boy would take his throne. He then abandoned his beloved wife, who bore the only boy, and moved to a new village with other wives having girl babies. The newborn baby boy climbs an oil palm tree and drops its fruit for his mother. This child was the hero god Kamangú, who was born with a small basket of magic on his shoulder.

At his mother's wish, he stops being a baby and goes hunting in the forest. In a trap he set in the den of an African giant rat, he obtained a set of iron blades. The next day, he finds a human hand captured in the trap. When he hesitates, a voice comes from the hole and says, “Hey, you coward!” He pulls the hand out and two young women come out to be his wives. One after another, more and more people are pulled out, and he is immediately placed in the throne of their village chief. He does not listen to his wives and finally lets out an old man carrying a large basket filled with evil lies. Contrary to the advice of his wives, the village chief then gets drunk on palm wine, falls into the old man’s tricks, and breaks the taboo. He taunted the villagers, “You have come out of a rat hole!”

When he woke up the next morning, he found no village nor houses, even a single person. He ran and jumps into the depths of the earth after his wives, rejecting the advice of his magical basket to give up. He crosses the great underground river and climbs a great tree. He reaches the heavenly world and makes wagtail his friend. His wives return to their native land of thunder. He is almost burnt to a crisp by the greetings of lightning by his kin, but with the help of the wagtail, he escapes and is welcomed as a guest. The trials brought to him one after another include falling a large tree with an axe without a handle and fighting with many monsters. The safari ants, the African weevil, the chameleon, and other creatures were all originally terrifying monsters. It is Kamangú’s miraculous power that made them as small as they are now with his magical songs. The story of Kamangú is endless, because his deeds of valor are engraved on every creature that lives in the forest.

When I came across the epic of Kamangú, I realized that many of the folktales I had heard before were fragments of this kind of mythological tradition. My interest was suddenly piqued, and I asked the village chief of the forest village who had adopted me, "Father, do you have such a long story?" I asked. The following is a synopsis of another heroic epic told by my adoptive father, Ngoli Musafiri Luapanya, in the Kuko dialect, which is located to the south of the Binja dialect.

Once upon a time, a human king hid his daughter in a palace with 12 doors and sent out a herald saying, “We will give our daughter in marriage to the brave warrior who opens all these doors.” The beasts of the forest try one after another, but no one succeeds. Finally, the smallest squirrel in the forest succeeds in opening the doors. On the way back to the village with his new wife, the beasts of the forest challenge the squirrel to a fight. However, antelope, leopard, buffalo, and even elephant are all thrown to the ground by the squirrel.

His pregnant wife wanted only the fruits of nsákú (African pear, Dacryodes edulis) tree in the forest. The squirrel went to pick them, and because of his several visits, he was killed in a trap set by the owner of the tree, a monitor lizard. The child in his mother’s womb spoke out that he would be born from her lap, and came out with his twin sister; the third to be born from the natural place was a chimpanzee.

As soon as he is born, he quickly grows into a young man and kills his father’s murderer. He sets out for the village downstream where his sister Patila has gone to marry. There, he is challenged by the relatives of her husband, but in the end, he beats them all to death in a football game in which they kick a giant rock ball at each other. At last, he used his magical powers to raise the dead, and there was no one left to stand against his power and wisdom.

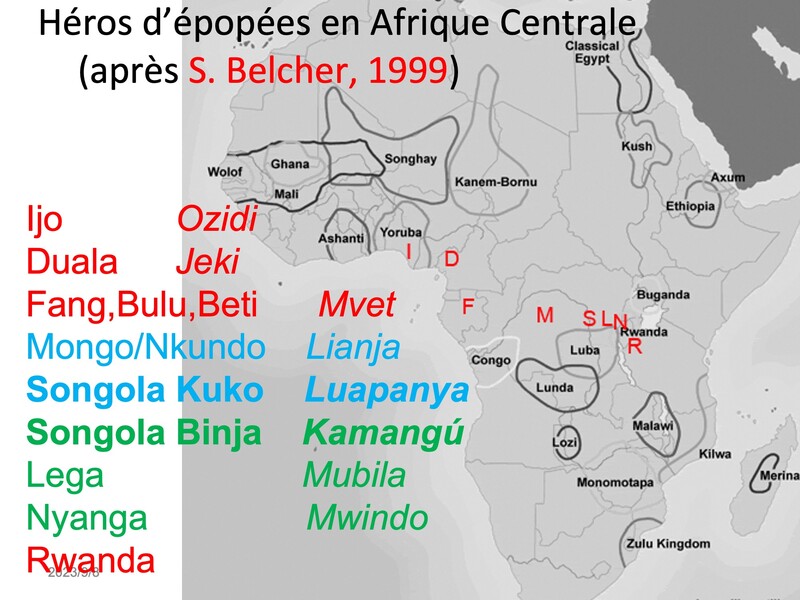

Although they share the ethnic identity of “We the Songola,” we found considerable differences in the heroic epic as told by the Binja and Kuko groups. Daniel Biebuyck, who studied the society and oral traditions of the Lega and Nyanga people of the eastern forests of the Songola, also reported on the heroic epics of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Biebuyck, 1972). In comparison, the epic of the Binja group, which begins with a conflict between a chief and a hero, shares many motifs with those of the Lega and Nyanga. On the other hand, the story of the Kuko group, which begins with a miraculous child who avenges his father’s death due to his wife’s morning sickness, has been handed down by each ethnic group in its own language, but in a broader perspective, it is similar to the Lianja, Boita’a ndongo, and other hero epics handed down among the Mongo ethnic groups west of the Lualaba River.

Thus, the two sets of epics handed down by the Kuko and Binja groups of the Songola people can provide clues to the history of ethnic migration among the forest peoples across the Lualaba River.

Biebuyck (1972: 273) wrote: “In listening to the epic, the Nyanga marvel and find pride and confidence from the epic. This is a truly ‘national’ patrimony.”

My adoptive father, Mr. Luapanya, did not tell us the epic hero’s name, but spoke of “He” in the third person. But the same epic, written in the Songola language in a notebook by another tradition holder, was entitled “Lwanu la Luapanya” or the “Tale of Luapanya.” When I saw it, I was reminded of a story of an adventurous journey into the kingdom of wild boars, which apparently constituted a part of the same epic cycles. Among the narrators of this tale, only Mr. Luapanya, my father, had told it in the first person. For the first time I understood why he did so. For the Songola, people who share the same name are one person, even if they live in different spaces and times. That was why he authorized himself to tell the Luapanya epic as his own. In Japan, it is a privilege for the descendants of emperors to have their own mythical epic of their ancestors, but among the forest peoples of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the way is wide open for the common people to live with their “cultural treasure” of marvelous heroic epics as their own patrimony.

Reference

Biebuyck, Daniel. The epic as a genre in Congo oral literature. African folklore (1972)

Un manuscrit à publier en japonais dans :

Takeuchi, Shin'ichi & Daiji Kimura (eds.) (2024). Cinquante chapitres pour connaître la République Démocratique du Congo, Akashi Shoten, Tokyo.

Epopées des héros de la forêt : Traditions orales du peuple Songola (RDC)

ANKEI Yuji (Institut pour la diversité bioculturelle, Japon)

Lorsque je vivais dans un village situé dans la forêt au long de la fleuve Lualaba, à 2 700 kilomètres de l'embouchure du fleuve Congo, j'aimais écouter le soir diverses traditions orales, telles que des contes populaires et des énigmes dont les animaux étaient les personnages principaux. C'est en 1983, lors de mon troisième séjour, que j'ai entendu pour la première fois une longue narration. Le récit durait 45 minutes. Le narrateur était M. Bitonde Kaombi, alors âgé d'une trentaine d'années, né et élevé à Kindu, dans la province du Maniema. L'histoire, racontée dans le dialecte Binja de Songola, sa langue maternelle, était une forme de grand art avec une présentation théâtrale vraiment vivante et de nombreuses chansons qu'il chantait avec son audience.

J'ai essayé de transcrire les enregistrements, petit à petit, en suivant les explications données dans le dialecte congolais du swahili. Le synopsis de l'épopée héroïque des Songola, qui n'a jamais été présentée au monde, est le suivant.

Il était une fois un chef de village qui avait épousé dix femmes. Il déclara qu'il ne voulait que les filles parce qu'un garçon prendrait son trône. Il abandonne alors sa femme bien-aimée, qui a porté le seul garçon, et déménage dans un nouveau village avec autres femmes et leurs filles. Le nouveau-né grimpe à un palmier à huile et laisse tomber son fruit pour sa mère. Cet enfant est le dieu héros Kamangú, qui naît avec un petit panier magique sur l'épaule.

À la demande de sa mère, il cesse d'être un bébé et part chasser dans la forêt. Dans un piège qu'il tend au repaire d'un rat géant africain, il obtient un assortiment de lames de fer. Le lendemain, il trouve une main humaine prise dans le piège. Alors qu'il hésite, une voix sort du trou et lui dit : "Hé, lâche !". Il retire la main et deux jeunes femmes en sortent pour devenir ses épouses. L'un après l'autre, de plus en plus de gens sont sortis, et il est immédiatement placé sur le trône de leur chef de village. Il n'écoute pas ses femmes et fait finalement sortir un vieil homme portant un grand panier rempli de mauvais mensonges. Contrairement aux conseils de ses femmes, le chef du village s'enivre alors de vin de palme, tombe dans les pièges du vieil homme et brise le tabou. Il raille les villageois : "Vous êtes sortis d'un trou à rats !"

Lorsqu'il se réveille le lendemain matin, il ne trouve ni village, ni maisons, ni même une seule personne. Il court et saute dans les profondeurs de la terre à la suite de ses femmes, rejetant le conseil de son panier magique de renoncer. Il traverse la grande fleuve souterrain et grimpe sur un grand arbre. Il atteint le monde céleste et fait de la bergeronnette son amie. Ses femmes retournent dans leur pays natal, le pays du tonnerre. Il est presque brûlé par les salutations de foudre de ses proches, mais avec l'aide de la bergeronnette, il s'échappe et est accueilli comme un invité. Parmi les épreuves qui se succèdent, il y a la chute d'un grand arbre avec une hache sans manche et la lutte contre de nombreux monstres. Les fourmis safari, le charançon africain, le caméléon et d'autres créatures étaient à l'origine des monstres terrifiants. C'est le pouvoir miraculeux de Kamangú qui les a rendus aussi petits qu'ils le sont aujourd'hui grâce à ses chants magiques. L'histoire de Kamangú est sans fin, car ses actes de bravoure sont gravés sur toutes les créatures qui vivent dans la forêt.

Lorsque j'ai rencontré l'épopée de Kamangú, j'ai réalisé que de nombreux contes populaires que j'avais entendus auparavant étaient des fragments de ce type de tradition mythologique. Mon intérêt s'est soudain éveillé et j'ai demandé au chef du village de la forêt qui m'avait adopté : "Père, avez-vous une si longue histoire ?" demandai-je. Voici un résumé d'une autre épopée héroïque racontée par mon père adoptif, Ngoli Musafiri Luapanya, dans le dialecte Kuko, situé au sud du dialecte Binja.

Il était une fois un roi humain qui cachait sa fille dans un palais à 12 portes et envoyait un héraut disant : "Nous donnerons notre fille en mariage au courageux guerrier qui ouvrira toutes ces portes". Les bêtes de la forêt essaient l'une après l'autre, mais personne ne réussit. Finalement, le plus petit écureuil de la forêt réussit à ouvrir les portes. Sur le chemin du retour au village avec sa nouvelle femme, les bêtes de la forêt défient l'écureuil. Mais l'antilope, le léopard, le buffle et même l'éléphant sont tous jetés à terre par l'écureuil.

Sa femme enceinte ne voulait que les fruits du nsákú (Dacryodes edulis) dans la forêt. L'écureuil est allé les cueillir, et à cause de ses nombreuses visites, il a été tué dans un piège tendu par le propriétaire de l'arbre, un varan. L'enfant dans le ventre de sa mère a dit qu'il naîtrait sur ses genoux, et il est sorti avec sa sœur jumelle ; le troisième à naître du lieu naturel a été un chimpanzé.

Dès sa naissance, il devient rapidement un jeune homme et tue le meurtrier de son père. Il part pour le village en aval où sa sœur Patila est partie se marier. Là, il est défié par les parents de sa sœur, mais il finit par les battre tous à mort lors d'un match de football au cours duquel ils se renvoient une balle de pierre géante. Enfin, il utilise ses pouvoirs magiques pour ressusciter les morts, et plus personne ne peut s'opposer à son pouvoir et à sa sagesse.

Bien qu'ils partagent l'identité ethnique "Nous les Songola", nous avons constaté des différences considérables dans l'épopée héroïque racontée par les groupes Binja et Kuko. Daniel Biebuyck, qui a étudié la société et les traditions orales des Lega et des Nyanga des forêts orientales des Songola, a aussi rapporté les épopées héroïques de la République démocratique du Congo (Biebuyck, 1972). Par comparaison, l'épopée du groupe Binja, qui débute par un conflit entre un chef et un héros, partage de nombreux motifs avec celles des Lega et des Nyanga. En revanche, celle de l'ethnie Kuko, qui commence par un enfant miraculeux qui venge la mort de son père due aux nausées matinales de sa femme, a été transmise par chaque ethnie dans sa propre langue, mais dans une perspective plus large, elle est similaire aux Lianja, Boita'a ndongo et autres épopées héroïques transmises parmi les ethnies Mongo à l'ouest du fleuve Lualaba.

Ainsi, les deux séries d'épopées transmises par les groupes Kuko et Binja du peuple Songola peuvent fournir des indices sur l'histoire des migrations ethniques parmi les peuples de la forêt de l'autre côté du fleuve Lualaba.

Biebuyck (1972 : 273) a écrit : "En écoutant l'épopée, les Nyanga s'émerveillent et y puisent fierté et confiance. Il s'agit d'un patrimoine véritablement 'national'".

Mon père adoptif, M. Luapanya, ne nous disait pas le nom du héros de l'épopée, mais parlait de "Lui" à la troisième personne. Mais la même épopée, écrite en langue songola dans un cahier par un autre détenteur de la tradition, s'intitulait "Lwanu la Luapanya" ou le "Conte de Luapanya". En le lisant, je me suis souvenu d'un récit d'un voyage aventureux au royaume des sangliers, qui faisait apparemment partie des mêmes cycles épiques. Parmi les narrateurs de ce récit, seul M. Luapanya, mon père, l'avait raconté à la première personne. Pour la première fois, j'ai compris pourquoi il l'avait fait. Pour les Songola, les personnes qui portent le même nom sont une seule et même personne, même si elles vivent dans des espaces et des temps différents. C'est pourquoi il s'est autorisé à raconter l'épopée de Luapanya comme s'il s'agissait de la sienne. Au Japon, c'est un privilège pour les descendants des empereurs d'avoir leur propre épopée mythique de leurs ancêtres, mais chez les peuples de la forêt de la République démocratique du Congo, la voie est grande ouverte pour que les gens du peuple puissent vivre avec leur "trésor culturel" de merveilleuses épopées héroïques comme leur propre patrimoine.

Référence bibliographique

Biebuyck, Daniel. The epic as a genre in Congo oral literature. African folklore (1972)