![]()

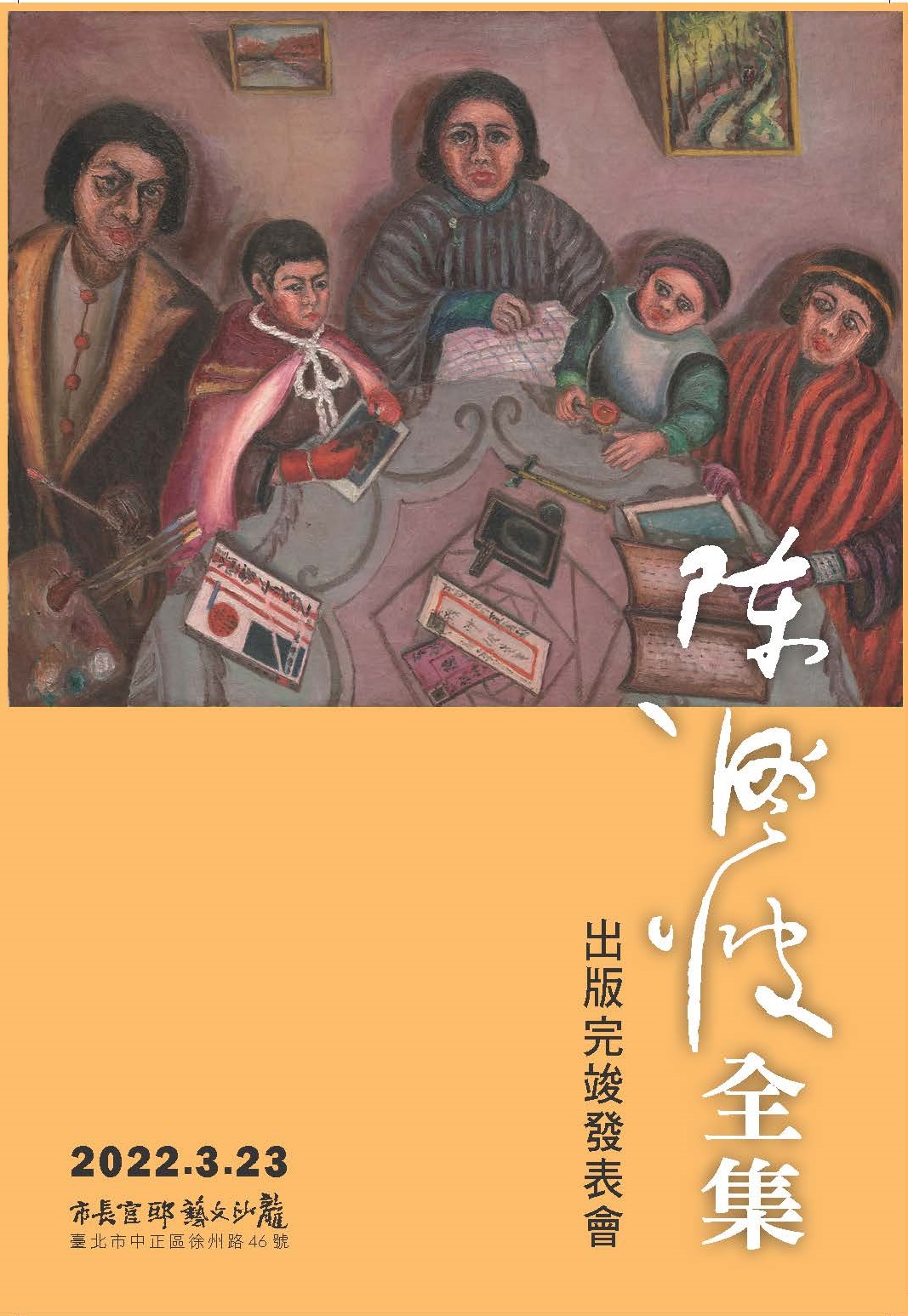

陳澄波全集)全18巻完結! 発表会の案内が届きました。 RT_@tiniasobu

2022/03/23

2021年9月に解説原稿を送った、台湾の画家・陳澄波全集 第11巻の校正と英語から中國語訳への翻訳が完成したと思ったら、それと同時に、全巻完結となることがわかりました。

http://ankei.jp/yuji/?n=2564 で書いていますが、この仕事を頼まれた日が狭心症に気づいた日でした。そのため、仕事が遅れてご迷惑をかけましたが、なんとか間に合ったということです。

|323,《陳澄波全集》出版完竣發表會|

2012-2022,耗時整整10年

《陳澄波全集》合計18卷,完工!!

對於編輯《陳澄波全集》的我們來?,10年好像很長。但與陳家人相比,他們?經藏匿、公開、修復這些作品、文件,花了65年的?月(1947-2012),我們這些後輩的10年,實在太短。

今年是陳澄波逝世75年,基金會沒有大型的紀念活動,僅以《陳澄波全集》的完成來還原一個藝術家本來面目。

3月23日(三)下午2:00,《陳澄波全集》出版完竣發表會,於市長官邸藝文沙龍舉行,邀請這一路上協助基金會的老師、夥伴們一同出席。

以下は、解説文の書き出しの部分です。 17ページ書いてといわれて、55ページかいてしまったのでした。

Teacher, Artist, and Politician: Chen Cheng-po’s Vocations as Hinted in

His Notebooks

ANKEI Yuji (安溪遊地), YOSHINAGA Nobuyuki (吉永敦征), IZAO Tomio (井竿富?)1

Introduction

A. Chen Cheng-po’s lifetime and his three notebooks

In the collection of Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation (the

Foundation),2 there exist three notebooks. The first notebook, labeled A

Collection of Essays (the Collection), was started on January 1, 1915

when Chen was a student at the Taiwan Governor-General’s Office National

Language School (National Language School) in Taihoku (today’s Taipei).

The second notebook, labeled “Philosophy” on its cover, was started on

April 27, 1926 when Chen was a third-year student at the Tokyo School of

Fine Arts. The third notebook consisted mainly of a long essay and was

labeled “Review (Society and Art)” (Review Notebook) and dated September

9, 1945. Whereas the first two notebooks were written in Japanese, the

third was in Chinese.

These are the rare records that have remained until today to tell us

what Chen Cheng-po wrote, apart from what he drew, in his school days

and afterwards.

Throughout his life, Chen Cheng-po had pursued the three ambitions of

becoming a teacher, an artist, and a politician. In an interview, his

eldest son Chen Tsung-kuang told Izao Tomio and his students from Japan

that his father had accomplished the first two ambitions with much

success, but the last ambition was a complete catastrophe that ended in

his being summarily uted during the 228 Incident (see Section 4C).

The above-mentioned three notebooks were respectively written during

times he was preparing to face new challenges of life.

Encouraged by Chen Tsung-kuang’s son Chen Li-po and other members of the

Foundation, we have worked since March 2016 to find out what were

written in Japanese in his notebooks, and

we wish to share our discoveries. Our investigation has been

supplemented by studying texts written on loose sheets of paper, on

sketchbooks, or in the margin of his books.

B. Chen Cheng-po’s Japanese handwriting

Before entering the public school in Chiayi at the age of 13, Chen

Cheng-po studied Chinese classics in a private school. At the Tokyo

School of Fine Arts, the characters in his calligraphy exercises were so

well balanced and neatly written that there was little correction from

his teacher. Though Chen’s calligraphy skill might have been passed down

from his father, who died in 1909, the handwriting in his notebooks is

hard to decipher because of the cursive style he employed.

Some characters are illegible because they are fragmentary, or because

the paper on which they were written has been torn. If we could get hold

of the original texts from which Chen Cheng-po had copied, we could

rebuild these characters, but only a few of the originals could be

found.

In the second notebook which Chen Cheng-po used for his philosophy and

education classes, the handwriting is even more difficult to decipher.

This is so probably because he had to jot down sentences which were only

spoken but not written on the blackboard. Also, as Chen Cheng-po had to

keep pace with the spoken words of his teachers, he had wrongly written

many characters in Chinese which had the same Japanese pronunciations.

He might have particular difficulties in writing down the names of

western scholars when they were written in alphabets of English, German,

Latin, or even Greek.

An abundance of mixed use of different forms of characters could be

found in the first notebook, examples include 歸?帰?? and 氣?気?气. Whereas 歸

and 氣 are in the formal style similar to present-day traditional Chinese

characters, 帰 and 気 are the popular versions which are mostly similar to

the kanji used in Japanese writings nowadays, while ? and 气 are abridged

versions not unlike the simplified Chinese characters of today. The

authors have mostly retained the different versions used in the original

script and have made no attempts to unify the character types. If there

are characters that are obviously wrongly written or mistaken, however,

the authors will provide the correct ones within parentheses and

underline them.

C. Difficulty of literary Japanese

In Chen Cheng-po’s days, written Japanese was far more difficult to

master than its spoken form than today, especially in the classical

style and in verses.

Let us take an example from a Japanese song that Chen Tsung-kuang chose

to sing with us on our request when we visited his home in Chiayi in

March 2016. The title of the song was Umiyukaba 海行かば (If I Go Away to

the Sea), being an extract from a long poem to praise

the emperor for the discovery of gold in the north. The poem was written

by 遵ユtomo no Yakamochi (ca. 718-785, 大伴家持), the learned

poet-administrator who compiled the first songbook of Japan, Man-y醇vsh醇・

(萬葉集). In the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, Chen Cheng-po was asked to

practice calligraphy on poems of his choice from this songbook. All the

nine poems he had chosen were the love poems exchanged between the poet

and a lady named Ki no Iratsume.

Japanese children including Taiwanese and Korean ones during the

Japanese colonial era were made to sing this song at schools, but most

of them misunderstood the lyrics.4 Ankei Yuji’s mother Fumiko was 18

years old in 1937 when she first heard Umiyukaba as if it were the

second national anthem. She wondered why this song mentioned about four

hippopotami. This explains why:

Original lyrics:

Umi yukaba mizuku kabane; Yama yukaba kusamusu kabane; 遵ユkimi no he ni

koso shiname; Kaerimi wa seji (If I go away to the sea, I shall be a

corpse washed up /

If I go to the mountain, I shall be a corpse in the grass / But if I die

for the Emperor, it will not be a regret.)

Sung by children as:

Umi ni kaba mimizuku bakane; Yama ni kaba kusamusu kaba ne; 遵ユ! Kimi no

he ni koso shiname (Hippos are in the ocean, owls are fools aren’t they?

Hippos in the hills are hippos smelling bad aren’t they? Oh, I am

determined to die from your fart!?

Fumiko also remembered another song that celebrates the birth of the

prince baby on December 24, 1933?Hitsugi no miko wa aremashinu (The

Prince to Succeed the Sun Dynasty is Just Born日嗣の御子は生れましぬ)?but was

understood by children as Hitsugi no miko wa aremaa shinu (Alas, the

baby in the coffin is dying! 棺の御子はアレマー死ぬ).