![]()

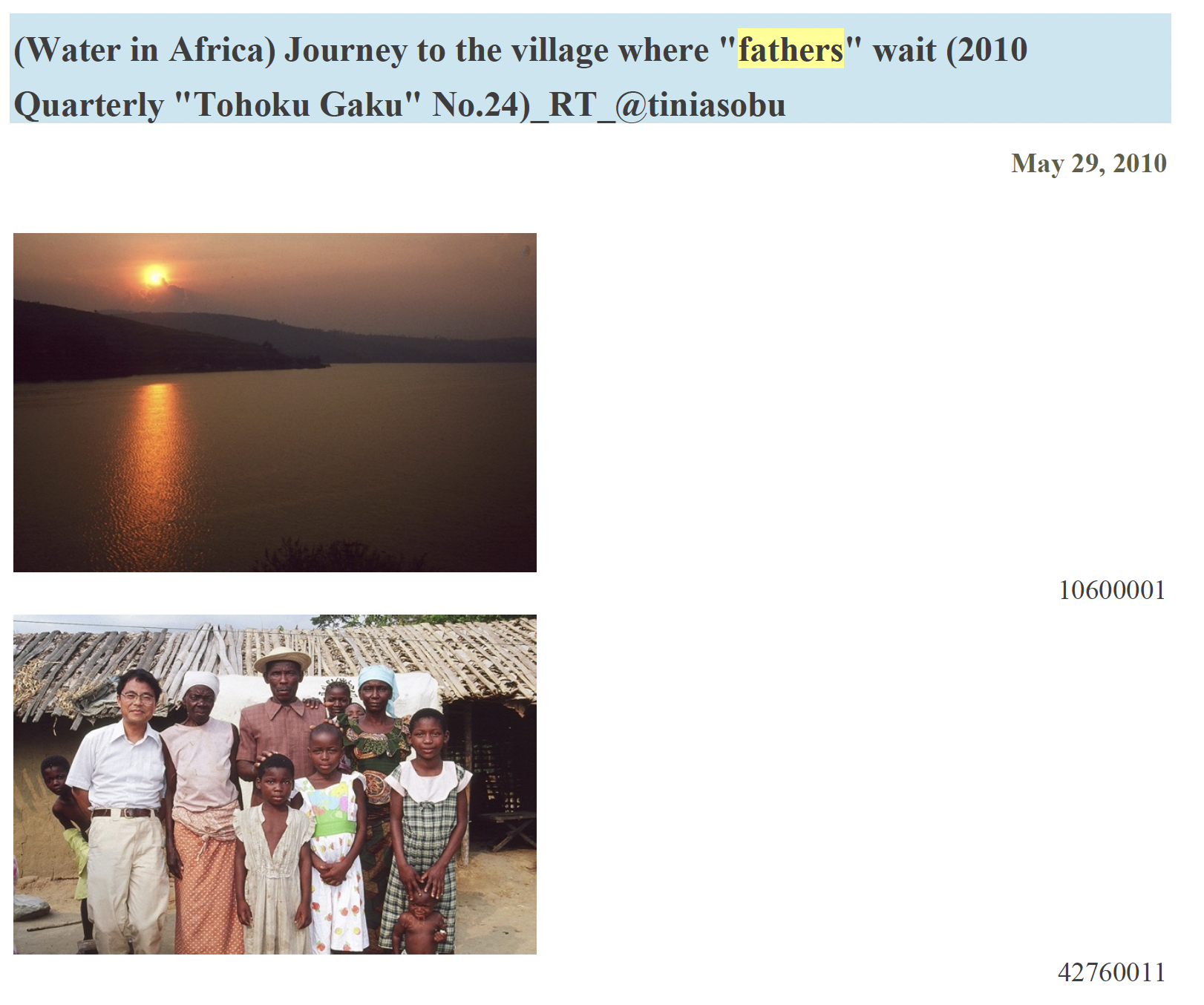

My fieldwork in the DR Congo-Zaire: Being adopted by a village chief RT @tiniasobu

2023/05/13

Français ci-dessous:

Voyage au village où nos pères nous attendent : expériences en Afrique

Once you drink African water, you will always return to Africa.

Translated from its Japanese version available in http://ankei.jp/yuji/?n=993

(Water in Africa) Journey to the village where "fathers" await (2010 Quarterly "Tohoku Gaku" No.24)_RT_@tiniasobuMay 29, 2010

Once you drink African water, you will always return to Africa. It is true. I wrote this article for "Tohoku Gaku" through a relationship with Mr. Norio Akasaka, who came to Yamaguchi Prefectural University to give a lecture.

The bibliographical note can be found here.

https://iss.ndl.go.jp/books/R000000004-I10789627-00

A Journey to the Village Where my Fathers Await: My Experience in Africa

Ankei Yuji

In 1972, when I was a third-year student in the Faculty of Science at Kyoto University, I felt frustrated with biology, which I had been aiming for, or even with being a university student itself. It was then that I learned of the mobile university movement started by anthropologist Jiro Kawakita and jumped into a two-week camp at the foot of Mt. Iwaki in Aomori Prefecture. In a program where 108 participants studied the region as their textbook, I experienced a great sense of freedom and was drawn to the fieldwork. The next thing I knew, I was a volunteer staff member of the mobile university and was busy preparing for the next year's Kakudahama Mobile University in Makimachi, Niigata Prefecture. I had never been able to read a timetable before, and over the next six months I spent 100 nights on the road, almost evaporating from my home in Kyoto.

When I returned to the university, I found that Dr. Junichiro Itani, a student of Kinji Imanishi, who was the same student as Dr. Kawakita, was promoting African studies there. I wanted to do fieldwork in Africa! With this thought in mind, I took the entrance exam for the graduate school of physical anthropology. I had no idea that I would go on to study the folklore of Okinawa and later become a university teacher of cultural anthropology. Takako, who had worked with me as a staff member at the mobile university, was engaged to be married and was about to change her major from microbiology to plant ecology. We visited Kanokawa Village, an abandoned village in the remote Iriomote Island, under the direction of Dr. Itani, and it became the field of our first joint research.

Dr. Itani accompanied me on three trips to Iriomote Island. Wading chest-deep in a mangrove estuary and camping for self-sufficiency in food were special training programs for me, who had thought that fieldwork was to listen to elderly people seated on the verandah. Bushwalking and stream climbing in the uninhabited mountains and fields was also a rehabilitation program for Dr. Itani, who was tired of meetings and writing manuscripts.

We went to Iriomote Island for three years (30 years after returning from Africa) before our long-cherished dream of going to Africa was realized. Iriomote Island became an important place where we learned the basics of the study method, which is to have a close relationship with local people and to conduct joint research in the same field from different viewpoints. During that time, we had the unforgettable opportunity to learn directly from Dr. Tsuneichi Miyamoto at the Daisen Mobile University about the fieldwork ethics (Miyamoto & Ankei, 2006).

As we neared our departure for Africa, Dr. Itani told us,"No matter how coarse the mesh is, you have to do research that covers a topic as a whole. If we do that, you will find a problem that no one has tried to solve before. When you find it, concentrate on that one spot and dig deep, until you reach bedrock. A good place to start would be the forest east of the Lualaba River. That's where no one has ever done anything before. ......" "Dig deep where you stand! Underneath lies a fountain!" are the words of Nietzsche (1963, p. 22) and of Iha Fuyu, the father of Okinawan studies, whose pen name was "Kansen (Sweet spring)". The field that Dr. Itani selected for us, based on what he saw of the beautiful forests he had flown over it in an airplane, was about 2,700 km up the Congo River from its mouth, in the middle of the tropical rainforest in the heart of Africa. Would it really be a place where we could "stand"?

Dr. Itani had devised a way to raise travel expenses for the two of us, and for those of us who had never done overseas research before, he arranged for Makoto and Eiko Kakeya who were senior students in our laboratory, to accompany us and guide us until we found a village where we could settle down.

In the forest villages inhabited by the Songola people, the four of us were welcomed with hospitality. We were accommodated in the best rooms, served a feast, and never once asked for a payment. The 10-day walking trip was filled with encouraging nudges from our senior colleagues, such as shaking hands with an old lady who had no fingers at all due to leprosy, or stepping into a swarm of safari (driver) ants and getting bitten all over when we looked up when they said in Swahili, "Let's watch the birds." On our last day, we walked 38 kilometers along a forest trail, carrying all of our luggage, including dishes and pans. When we reached the opposite bank of the hotel in the town of Kindu, it was nightfall. We finally caught a wooden boat that would take us across the night river, which was 600 meters wide. However, after they started rowing, the boatmen charged us an exorbitant price, four times what they had promised (100 times the ferry fare in the daytime). They rowed us to a dark sandbar and asked us if we would like to sleep there for the night. “The crocodiles around hear have big bellies" they said. I was furious, but Kakeya, in a calm, coaxing voice, began bargaining, saying, "Tutakubariana (Let's compromise)," and we agreed to pay about one-third of the original price.

Based on this trip, we chose a village called Ngoli having less than 100 people where we were welcomed with clean beds and a strong local drink. Sometime later, Takako and I returned there and asked if we could stay with them for six months. The conversation was in wobbly Swahili. I was greeted with a warm smile, and the village head gave us his own room. Takako was soon welcomed into the world of the village women, and we began to live under the care of the village chief's two wives, who provided us with food and a bucket of water to bathe in each day. Takako gradually began to speak Swahili, a language she had never learned in Japan. Staying as a couple, the host family seemed to feel at ease with us.

Takako's idea was to not use a camera or tape recorder for the first month until the villagers became accustomed to us. After a couple of weeks, the village head asked if he could build us a house. He must have realized that we were serious about our request to live there for six months. We were overjoyed and decided to have him build us a house. We chose a place on the outskirts of the village. They cut the grass, drove stakes, and shaped the house with ropes, and we were ready to go. The house, including the kitchen and bedroom, was just enough to contain us. However, the construction work did not start. The grass grew back on the planned site and the rope was hidden in it. I couldn't wait any longer and asked the village head why the construction work had not started.

If the reply had been, for example, "We don't have the manpower or materials," or "The procedures for the Housing Loan are in progress," we would have been prepared to compensate for it.

However, the reply came from an unexpected direction. He said, “Many children call me 'father,' but they are all my brothers' children. As a matter of fact, none of them are my own children. ...... Won't you be my son?" I was so taken by the momentum of the conversation that I unintentionally answered in Swahili, "Ndiyo," or "Yes." Then he said, "Then you are my son from today. If you are a son, you should live with your parents. So there is no need to build a new house." Thus, our dream of owning a house vanished.

From then on, we had to call the village head "Baba" (father) or "Asá" in the local Songola language, instead of "Sultani" (village head) in Swahili. Not only that, we were taught that elder brothers were "elder fathers" and his younger brothers were "junior fathers," and that if there is only one chair, for example, I must naturally give it to my father. The youngest father introduced to me was a boy of about six years old at the time.

Some time after I became the son of the village head, a large gathering of neighboring Protestant congregations was to be held in a nearby village. When we approached the venue after a three-hour walk, my father was among the many people waiting to welcome us, and he called out, "My son!" I had no choice. I ran to him, shouting, "Father," and hugged him in public. This was a performance to let the village chief, who had never had a son, know that he finally had a son.

To begin our fieldwork, we decided to make a map of the village. Takako, who has a better sense of direction than Yuji, drew the map. I could hear the villagers whispering, "Wow, the wife does the work that requires a lot of brain power, doesn't she? The villagers' impression of me became definite when I prepared botanical specimens to investigate the relationship between the forest and humans. While Takako collected and sketched the plants, I continued to make dried specimens while stoking the firewood. When I visited a house to interview the family members, I was told, "Your job is to dry leaves, isn't it? You should leave such difficult things like writing to your wife," I was told. Still, I managed to ask one house at a time, and when I came to my own house, I asked my father as I did in other houses." How many children do you have?" He replied, "Just you." We then entered the house across the street of a man with seven wives. He offered me a chair and served me distilled liquor. Since we chose the village for its strong liquors, I took it without hesitation. Then my father's second wife came in and in a harsh voice ordered me to go home immediately because my father was calling for me. I rushed home and received a sermon from my father.

“My family and the family across the street have an important and serious relationship, as both of us are marrying wives from the other. You must not drink alcohol with them." Thus, I knew that the village was divided into two kinship groups

In cultural anthropology, this is called a "avoidance relationship," the wisdom of cooling down a relationship that might otherwise be easily damaged. The strictest type of avoidance relationship is, the relationship between a man and his wife's mother. For example, it is considered rude even to meet her on the street, and if such a situation arises, the husband is expected to hide in the bushes as a sign of respect, and avoid showing himself to her. Although not as strict as this, there are some relationships where eating from one plate is not allowed. As a result of our being caught up in the weave of village kinship, we have made the choice that we were only allowed to interact in a relaxed, joking manner with only half of the villagers.

Between father and son, we are allowed to eat from one plate, but there was still something to be avoided. We lived by the principle of not paying rewards in money in the village. For example, I would give my father a few cigarettes, although I did not smoke in case he carried firewood for drying plant specimens to study my knowledge about the forest. I sometimes gave my father cigarettes as a sign of respect, but for the first time he asked me, "Well, when do you smoke?"

I answered, "Dad, I smoke at night, inside the house."

On a day when the rain that had been going on for a while cleared up, I found my father selling cigarettes on a roadside stone, drying them in a row, and I asked him without thinking.

“Father, when do you smoke?" “My son, I smoke at night, inside the house." This was a slightly awkward exchange of avoidance relationship.

The opposite of this is a somewhat strange term, "joking relationship." From the day I became a child, my father's sisters and aunts began to come to me in turn, insisting that I drink alcohol and buy snuff. I asked my father's wives about this, and they told me that my father's sisters and I, their nephews, were free to beg each other for anything and to freely exchange sexual jokes with each other. The same is true between my grandfather and his grandchildren. This is why oral traditions are sometimes passed down from generation to generation, even to the grandchildren.

When you are in this kind of weave of avoidance and joking relationships, many things can happen. One of the aunts would ask me to go into her son's room to check on him because he seemed to have fallen ill. She could not enter her son's room, but I could.

During the course of my long stay, the food at my father's house gradually became scarcer and scarcer. My grandfather, who lived just across the street, and I had a joking relationship, so it was easy for us to beg for anything, and he was always willing to treat us to a meal, so we often ate there. Then, my father called out to me.

“I thought you guys don't eat at your own house much these days, but I heard you eat at my father's. Why on earth?" I was at a loss for an answer, so I said honestly, "Because my father and my big mama (senior wife) doesn't eat much at home.

But this was taken as an accusation against the village court, which was held every Sunday. In the blink of an eye, I was the plaintiff and the first wife was the defendant. In the village square, surrounded by the villagers, arguments, speeches, testimonies, proverbs, and songs were repeated. As I watched in amazement, the elders deliberated and passed a verdict: "The children should be fed properly. The plaintiff won the case, saying that the children should be fed properly.

Immediately after the verdict, women around me poured sand on my head. It seemed they held sand in their hands before I knew it. They said, "Good luck should be balanced with bad ones. Don't get arrogant just because you have won." I remembered that a man who had won a small case had been poured by the sand-picking women. Later in my trip, when my father gave birth to his first daughter (my sister) on the same day I arrived in the village, I was also pelted with sand and told, "If it were a boy, you would have received heavier sand storms, congratulations!"

After the first six months of stay, on the day we left the village to return home, we gave away our personal belongings to those who had taken care of us. Immediately after that, I was called into my father's room and was scolded.

“You gave that machete to my father. I wanted it for myself." “Papa, I gave it to my grandfather because he asked me to give it to him. If you wanted it so badly, you should have told me. ......"

"How can a father ask his son to give him something! It's a shame."

A son should have given things to his father so that his father would not utter what he wanted from his son. Especially, giving gifts in public was to be avoided because the eyes of those who did not receive the gifts would be jealous and bring misfortune. The word for envy in the Congolese Swahili language is kilicho, which also means "big eyes."Fatherhood

Once adopted, there is no way to terminate the relationship.

We were only allowed to investigate within the pre-determined range of relationships. It was hard work to collect firewood to make over 1000 botanical specimens, and our stay meant asking father's second wife, who had a painful leg, to fetch water for every day. So we decided to hire a boy as an assistant. However, when they saw the boy, both mothers said in unison, "He has a bad character of a thief. If you need a boy, think of us as your boy and ask us for anything you want, okay?" So they said, and we were back to our old ways.

A young man who seemed to have some free time came to the village, and we walked together for about two hours to the next village and visited a store. Immediately my father called out, "Son, you are going out with that young man. The young man's fathers had all died, and he is an orphan. I am sorry for him, but you should know that he is freed from all the worldly constraints of how he should behave in front of his father.

Since you are not an orphan, you must not make a mistake of imitating his behaviors."

Having a "junior father" who was about 20 years younger than me, I entered a life in which I was probably blessed with "no lack of fathers in life." So when I told the villagers that I had only one father and one mother in Japan, they were badly shocked to hear. They said, “We could not live in such a chilly and lonely place." From their point of view, our one-father-one-mother kinship was quite strange. I studied the agricultural system of the forest village and the fish names of the riverside fishing village, and the barter economy that links different living environments. Takako studied cooking and alcohol brewing and their relationship to the plant world. Father said, "There is a riverside village where my brother's daughter, your sister, is married to a chief of the village, so you can stay there."

For the village chief of that riverside village, I was a member of his extended family who had given his wife in exchange for bride wealth of 10 goats. The relationship between me and the chief was more formal than that between a father and his son.

One day after a rain, I slipped on the wet soil in the courtyard of my sister's husband's house where I was staying and almost fell in front of him. The villagers, seeing this, said to me, "Too bad, we missed a goat!"

If I did slipped down, the husband of my sister should have helped me up and give me a goat as compensation for the shame I had experienced of falling in front of him, and the whole villagers could eat it. Also, although my father and I were in an abject relationship where we were not allowed to say "give me things" to each other, we still could eat from the same plate and were able to eat a chicken together. My sister's husband and I was not allowed to eat together from the same plate. The chicken would be brought to the table in a pot containing all the parts of a chicken, and a guest would be free to choose what he wanted to eat, after which it would be distributed among the family members. Chickens have hearts, livers, and other tasty parts that are too small to be shared, so this was done to avoid any embarrassing disputes that might complicate the important but delicate relationship between the relatives in marriage.

In the course of my research on the folk knowledge of fish (Ankei Yuji, 1982), I also interviewed my sister's husband. And when I happened to ask him the name of the fish excrement hole, he stammered in embarrassment. Oh, no! Such a question is no problem between two people who are in a joking relationship, but it was not to be uttered between two people who are in an avoidance relationship. Also, when I was learning the knowledge of over 500 forest plants from one of my fathers, I asked him the name of a certain plant, and he did not reply, saying that it was a disgrace. When Takako asked the mothers later, they told her that it was a plant with a sex-related use (Ankei Takako, 2009). Being caught in a kinship knot in the field like this had two sides: one was that the research went smoothly, and the other was that it was restricted in unexpected ways.

My third visit to Congo was in 1983. My son had just been born, so Takako stayed in Japan with our baby. When I arrived at the village, I immediately reported to my father: "Father, your grandson has been born." I realized that I had made a terrible mistake. On asking the name of the baby, my father was so disappointed, listing his three names: "Not Ngoli (free man), Musafiri (traveler), or Luapanya (mythological hero). ......"

At that moment, heavenly help descended to me.

“We gave him your Momámbá (name for the drum language) bobobo bobébo bobo (Luapanya Bungúu Kungwa)!"

Hearing this, my father's reply, with a big smile on his face, was astonishing. “At last you gave birth to me!" From that day on, my name in the village changed and I became "Father of Ngoli".

Mothers also began to say, "Your son calls you," instead of "Your father calls you." In other words, those who share the same name are the same person, and as long as a co-name owner is alive, they have immortal life even if their bodies perish.

Living the Myth

During my third stay, I realized for the first time that there is a long heroic myth in the Songola language. The man in his thirties who told me the myth was a masterful and dramatic storyteller, weaving a series of magical songs that brought forth miracles and wonders into the Hercules-like adventures of the culture hero Kamangú who was miraculously born as a brother to a chimpanzee. Explored the underworld to the Land of Thunder. As I chanted along with the audience by the fireside at night, I felt that ancient Japanese myths like Kojiki must have been told as a play in this way, with the sung parts being chanted by the audience. I planned a 100-kilometer trip to a village deep in the forest where this tradition is said to still flourish today, and consulted my father about it.

My father's reply was, "I can tell you that too." The myth that my father told me was different from the Kamangú myth, however, in that it began with the story of the smallest squirrel in the forest who overcame all the beasts to win the king's daughter, and the squirrel's child grew up to become a fierce god like Susanoo in the Japanese myths.

"Father, why didn't you ever tell me there was such a myth?" I asked him, "Why didn't you ever ask me? My father replied, He did not tell me the name of the raging god, but a court judge who happened to be in the village, at my request, wrote it down in his notebook and then read it to me. The myth was almost identical to the one my father had told me, except that the repetitions were omitted and the songs were shortened. The only difference was that he told us that the name of the raging god was Luapanya. It was at this point that I realized that the tale of an adventures in the land of the wild boar, which I had heard several times during the nighttime mists of my previous stay, was a fragment of this heroic myth, and I suddenly remembered that only my father had told it in the first person.

The hero of that part of the story was Luapanya, so my father of the same name told the myth in the first person as his own adventure. The heroic deeds in the myth of Luapanya were his own deeds and those of my son, who also bore the name Luapanya. I had felt a certain discomfort in the oral tradition of the Ainu people, told in the first person by a non-human deity Kamui, slowly dissolve within me.

The myths of the Songola people, which are still vividly told today, do not tell of a distant past, but are directly related to the way we live today, nor was only one version of the myths authorized and written down, nor were only the king's family privileged to be affiliated with the heroes of the myths. These myths are the dreams of the people of the land, which they have maintained through the great hardships of colonization and repeated civil wars. The task of writing down the myths was a challenge with the Songola language, a minority language for which there were no dictionaries or grammar books, and with the unknown Songola culture for which our only previous research was an ethnography published by a colonial administrator in 1909.

The Wish of a Migratory Bird

In 1990, I returned to the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where my father lived, for the first time in seven years. It was my fourth trip. After getting off the plane and entering the hotel, I immediately wrote a letter for the village where my sister lived. A boatman on a dugout canoe heading downstream agreed to carry that letter. However, rumors circulated that a murder had occurred in the village and that the people had been dispersed by avengers and looting by soldiers who took the name of interrogation, leaving the village almost abandoned.

My sister's village was a village that believed in Islam in 1980, but one day converted to Catholicism, and by 1983 the men were drinking distilled liquor in addition to the palm wine they had been accustomed to. Since that liquor was made by the women, a channel was created through which income was transferred from the men to the women, but I feared that there were certain dangerous pitfalls in this change. I had a hunch that perhaps the cause of the abandonment of villages was alcohol drinking.

So, I decided to almost completely abstain from alcohol myself. The first thing I did was to advise the village head, my sister's husband, to either stop drinking or at least to cut down on alcohol consumption. When I arrived in the village, I found that the murder had been the result of a fight over alcohol. People were slowly getting back to normal, but some of the women were drowning in spirits.

When I spoke to the village chief, my sister's husband, I found that he was somewhat depressed and felt that it did not matter where he died. Mr. Bernard, the husband of the chief's sister, was very worried that if the village disappeared, the immigrants might take ownership of the entire forest east of the Lualaba River. So he asked me if I could somehow encourage the village chief to help him revive the village.

The year before, we had crossed the line as researchers by starting a business of producing and selling pesticide-free rice on Iriomote Island, Okinawa (Miyamoto & Ankei, 2008). This time I decided to start a village revitalization project together with the chief's advisor, Mr. Bernard. Of course, textbooks of anthropology tell us that it is correct for fieldworkers to objectively record such incidents and social changes. However, Mr. Bernard was the pilot who had guided me on a wooden canoe trip of 250 km up the Lualaba River seven years earlier, in 1983, and he had saved my life on that arduous journey. And it is my sister's village that is about to be abandoned.

I spoke to the village chief about the importance of abstaining from alcohol rather than enjoying it, and that he could not persuade people to stop drinking if he himself was drinking. I mentioned that our god Kamangú in the myth of Songola had broken a taboo by getting drunk. I also told him that if the village were to be abandoned during his rule, in the unlikely event that we were to be deprived of our rights to this forest, the story would be passed down to the next generations, saying, "This happened in that chief's generation." After this persuading conversation, I could listen to him say, "We shall manage to try again."

Then, there was the matter of receiving out the imprisoned people, paying the fines for the confiscated guns, and x-rays and treatment for the village chief himself, who had a cough that would not stop. I had never given money in such situations before, but now that I had spoken up, I also decided to give the money needed for the village's recovery. So I followed the pattern of behavior at Wildcat-Brand Iriomote Island's Organic Rice in Okinawa.

I went further to my father's village in the forest. My father, whom I had not seen for a long time, was blind in one eye from an illness and looked old and feeble. He had wondered why I did not come to see him for as long as seven years. “Whenever I saw the moon in the sky, I could not help thinking of you. Come, let's eat from one plate," he said. However, my village was in a great turmoil. I am not at liberty to tell you about our family troubles, but one of my younger brothers was making a big fuss every day, yelling and screaming that he was going to take his case to the town court. He was the most relied upon by my father, and it seemed certain that he would inherit the position of village chief from my father in the next generation. It all started when his father hid his quarreling partner from him. The village chief's unyielding rule as a refuge was that "those who escape into the hands of the village chief would never die."

The younger brother, angered by this, sued his father to the town court. As a result, the father was imprisoned and had to give up both money and goats in order to be released. The father said that he could not allow a fool to take over the position of village headman, who would lose his property that would normally be his in the form of bride wealth for his own weddings. So, my father appointed a former slave who had been deprived of knowledge of his roots and his native language as the deputy village chief. The younger brother, angry at the choice, tried to sue the deputy chief. My sister's village was almost abandoned, and my own village was in such a turmoil. If left unchecked, even my own village might be abandoned. ...... I was so worried that I called my younger brother to talk to him. I asked him, "Do you know why father insisted on a former slave to take over as village chief ?" I asked. "Because, although I feel sorry for him, nobody would believe his choice to be serious. In Songola, there is a saying in our mythology that teaches us that "mo.kota tá.móne tá.kui" (a village chief neither sees nor hears), that is, to remain calm and not to be distracted by trivial matters. You were once a deputy chief of a village, don't you know that the more you fuss about every little thing like a trial, the more your father will be disgusted with you? The position of village chief is like an oil palm tree that grows abundantly in this village. If you stay quiet, the seed will fall under the tree and grow back there. If we create a storm, the seeds will fly away and grow far away from the trunk." After talking for a while, he said,"I understand now, brother. I'm sorry. I will apologize to our father."

The next day, my elder brother (the son of my father's brother), whom Takako and I trusted the most, arrive on foot to see us from a town about 30 kilometers away. That evening, as I was talking to my elder brother and father, it occurred to me to tell them this impromptu story in Swahili. It was raining outside, and wives staying indoors could not listen.

I told them a story.“Once upon a time, there was a forest of oil palms just like this village. There was a tall palm tree in the forest, and birds would come even from far to nest in it. One day, however, the leaves and roots of the palm had a conflict. The leaves insisted on not casting shadows on the roots, and the roots insisted on not sending water to the leaves. In the meantime, the trunk began to wither and rot. One night, there was a storm, and the mighty oil palm suddenly snapped in the middle. Then, the next time a migratory bird comes along, where on earth should it nest?"

"This is not an old tale. This is an appeal to the court," my father muttered, and both audience fell silent. I was afraid I had screwed up. Perhaps it was something a son should never say to his father. I withdrew into my room without even saying hello.

The next morning, however, my elder brother came to me. He said, "I was really impressed with your story of last night. Our father is thankful for you, citing the proverb, 'A son from afar has filial piety. You are the very person of this village. Your body may have been born in faraway Japan, but you are originally from this village. Your parable was like a sharp spear penetrating our hearts, and neither my father nor I had a word to say in reply. We will call all our family together next time, so please let them hear it again. ......

More than 20 years have passed since then without me being able to stand in my home village. Now that I have sent my parents off in Japan, I long for the warmth and nostalgia of a large African family. During my stay in Kenya in 1998, my family and I tried to visit the village where my father and his family were waiting for us, but we had to give up the idea two days before our departure from Nairobi due to the outbreak of civil war. Since then, we has spent our days visiting countries with forests, such as Kenya, Uganda, and Gabon in West Africa, hoping that peace will come to the people in the forests of my second homeland.

References・Takako Ankei, 2009, "Dialogue with a Forest People: An ethnobotany of the Lives of the Sungola People of Tropical Africa," TUFS AA Research Institute (in Japanese)・Ankei Yuji, 1982, "The Fish Cognition

of the Zaire River and Lake Tanganyika Fishermen," African Studies, Vol. 21 (in Japanese)Nietzsche, 1993, "Yorokobashiki kenkyu (Nietzsche's Complete Works 8)," Chikuma Shobo (in Japanese)・Miyamoto, Tsuneichi and Ankei Yuji, 2008, "The annoyance of being surveyed - a book to read before going into the field)," Mizunowa Publishing Co. (in Japanese)

Une fois que tu aure bu de l'eau africaine, vous reviendrez toujours en Afrique.

La version japonaise est disponible à l'adresse suivante : http://ankei.jp/yuji/?n=993

(Eau d'Afrique) Voyage au village où les "pères" vous attendent (2010 Trimestriere 'Tohoku Studies' No. 24)_RT_@tiniasobu29 mai 2010

Boire de l'eau africaine vous ramène toujours en Afrique. Et c'est vrai. J'ai contribué à cet article dans 'Tohoku Gaku' grâce à un lien avec Norio Akasaka, qui est venu à l'Université préfectorale de Yamaguchi pour donner une conférence.

Références.

https://iss.ndl.go.jp/books/R000000004-I10789627-00

Voyage au village où nos pères nous attendent : expériences en Afrique

Yuji Ankei.

En 1972, étudiant en troisième année à la faculté des sciences de l'université de Kyoto, je me sentais frustré par la biologie, qui était mon objectif, ou plutôt par le fait d'être étudiant à l'université. C'est alors que j'ai entendu parler du mouvement de l'Université mobile fondé par l'anthropologue Jiro Kawakita et que j'ai participé à un camp de deux semaines au pied du mont Iwaki à Aomori, au Japon. Dans le cadre d'un programme où 108 participants étudiaient la région comme s'il s'agissait d'un manuel, j'ai ressenti un grand sentiment de liberté et j'ai été attiré par le travail sur le terrain. Avant même de m'en rendre compte, j'étais devenue membre bénévole du personnel de l'université mobile et j'étais occupée à préparer l'université mobile de Kakudahama qui se tiendrait l'année suivante à Makimachi, dans la préfecture de Niigata. Je n'avais jamais su lire un emploi du temps auparavant et, au cours des six mois suivants, j'ai passé 100 nuits en déplacement et j'ai presque disparu de mon domicile à Kyoto.

À mon retour à l'université, j'ai appris que le professeur Junichiro Itani, un élève du professeur Imanishi Kinji, le même professeur que Kawakita, promouvait les études africaines à l'université. Je veux faire du travail de terrain en Afrique ! C'est dans cette optique que j'ai posé ma candidature à la faculté d'anthropologie physique. Je n'avais jamais imaginé que j'étudierais le folklore d'Okinawa et que je deviendrais plus tard professeur d'anthropologie culturelle à l'université. Takako, qui travaillait avec lui à l'université mobile, était sur le point de passer de la microbiologie à l'écologie végétale. Sous la direction du Dr Itani, nous avons visité Kanokawa, un village abandonné sur l'île d'Iriomote, qui est devenu le site de notre première recherche commune.

Le Dr Itani nous a accompagnés lors de trois voyages sur l'île d'Iriomote. Camper dans des estuaires de mangroves, avec de l'eau jusqu'à la poitrine et en autosuffisance alimentaire, a été un programme d'entraînement spécial pour moi, car j'avais toujours pensé que le travail sur le terrain consistait à s'asseoir dans une véranda et à écouter des personnes âgées. Les randonnées dans les montagnes et les champs inhabités et l'escalade des cours d'eau ont également constitué des programmes de réhabilitation pour le Dr Itani, qui était fatigué des réunions et de la rédaction de manuscrits.

Nous sommes restés sur l'île d'Iriomote pendant trois ans (30 ans après notre retour d'Afrique) avant que mon vieux rêve d'aller en Afrique ne se réalise. L'île d'Iriomote est devenue pour nous un lieu important où nous avons appris les bases de la méthodologie de recherche - en maintenant des relations étroites avec la population locale et en menant des recherches en collaboration à partir de perspectives différentes dans le même domaine. Pendant cette période, nous avons eu l'occasion inoubliable d'apprendre l'éthique du travail sur le terrain directement auprès du Dr Tsunekazu Miyamoto de l'Université mobile de Daisen (Miyamoto & Ankei, 2006).

À l'approche de notre départ pour l'Afrique, le Dr Itani nous a dit. Quelle que soit la taille de la maille, vous devez mener une enquête qui couvre l'ensemble du sujet. Si nous faisons cela, nous trouverons un problème que personne n'a essayé de résoudre auparavant. Une fois que nous l'avons trouvé, nous nous concentrons sur ce point et nous creusons plus profondément jusqu'à ce que nous atteignions la roche mère. Un bon point de départ serait la forêt à l'est de la rivière Lualaba. C'est là que personne ne l'a encore fait ! En dessous, il y a une source" est une citation de Nietzsche (1963, p. 22) et le nom de plume du père des études d'Okinawa, Fuyu Iha. Le terrain que le Dr Iya a choisi pour nous, en se basant sur les forêts spectaculaires qu'il voyait d'en haut, se trouvait au milieu d'une forêt tropicale humide au cœur du continent africain, à quelque 2 700 kilomètres de l'embouchure du fleuve Congo. Serait-ce vraiment un endroit où nous pourrions "nous tenir debout sur nos deux pieds" ?

Le Dr Itani a trouvé un moyen de couvrir les frais de voyage pour nous deux et, comme nous n'avions jamais fait de recherche à l'étranger auparavant, il s'est arrangé pour que Makoto et Hideko Kakeya étudiants en dernière année dans notre laboratoire, nous accompagnent et nous guident jusqu'à ce que nous trouvions un village où nous pourrions nous installer.

Nous avons été accueillis tous les quatre dans un village forestier habité par le peuple Songola. Nous avons été logés dans les meilleures chambres, avons eu droit à un festin et n'avons jamais demandé de paiement. Nos dix jours de marche ont été marqués par les conseils rassurants de collègues expérimentés, qu'il s'agisse de serrer la main d'une vieille dame qui avait perdu un doigt à cause de la lèpre ou de marcher dans un essaim de fourmis safari (fourmis foreuses) et de se faire piquer de tous les côtés, tout en disant "regardez les oiseaux" en swahili lorsque nous levions les yeux. Le dernier jour, ils ont marché 38 km le long d'un sentier forestier, portant tout leur équipement, y compris la vaisselle et les casseroles. Lorsque nous avons atteint la rive opposée de la rivière à notre hôtel dans la ville de Kindu, l'aube s'était levée. Nous sommes finalement montés à bord d'un bateau en bois qui nous a permis de traverser la rivière de nuit, large de 600 mètres. Cependant, lorsque nous avons commencé à ramer, le batelier nous a fait payer un prix exorbitant, quatre fois plus que ce qu'il avait promis (100 fois plus qu'un ferry-boat de jour). On nous a fait ramer jusqu'à un banc de sable sombre et on nous a demandé si nous voulions y passer la nuit. Ils m'ont dit : "Les crocodiles du coin ont un gros ventre". J'étais furieux, mais Kaketani, d'une voix calme, a commencé à négocier "tutakbariana" (faisons un compromis) et nous avons accepté de payer environ un tiers du prix initial.

Sur la base de ce voyage, nous avons choisi un village appelé Ngori, avec une population de moins de 100 personnes, où nous avons été accueillis avec un lit propre et une boisson locale forte. Quelque temps plus tard, Takako et moi sommes retournés au village et avons demandé si nous pouvions rester avec eux pendant six mois. Les conversations se sont déroulées dans un swahili approximatif. J'ai été accueilli par des sourires chaleureux et le chef du village nous a donné notre propre chambre. Takako a rapidement été accueillie dans le monde des femmes du village et nous avons commencé à vivre sous la responsabilité des deux épouses du chef. Peu à peu, Takako s'est mise à parler le swahili, une langue qu'elle n'avait jamais apprise au Japon. Nos familles d'accueil semblaient soulagées que nous soyons hébergés par un couple.

L'idée de Takako était que nous n'utilisions ni appareil photo ni magnétophone pendant le premier mois, le temps que les villageois s'habituent à nous. Quelques semaines plus tard, le chef du village nous a demandé s'il pouvait nous construire une maison. Il a dû se rendre compte que nous envisagions sérieusement de vivre là pendant six mois. Nous avons accepté avec plaisir de lui construire une maison. Nous avons choisi un endroit en bordure du village. Nous avons coupé l'herbe, planté des piquets, façonné la maison avec de la corde et elle était prête. La maison, y compris la cuisine et la chambre à coucher, était juste de la bonne taille pour que nous puissions y vivre. Cependant, les travaux de construction n'ont pas commencé. L'herbe poussait sur le terrain et la corde s'y cachait. Je n'ai pas pu attendre plus longtemps et j'ai demandé au chef du village pourquoi les travaux de construction n'avaient pas commencé.

Si j'avais reçu une réponse telle que "nous n'avons pas la main-d'œuvre ou les matériaux" ou "le processus d'hypothèque progresse", j'aurais été prêt à le dédommager.

Cependant, la réponse est venue d'une direction inattendue. Beaucoup de mes enfants m'appellent "père", mais ce sont tous les enfants de mes frères. Je n'ai pas de vrais enfants. Ne veux-tu pas être mon fils ?" Pris dans l'élan de la conversation, j'ai involontairement répondu en swahili "ndiyo", c'est-à-dire "oui". Il m'a alors dit. Si vous êtes un fils, vous devez vivre avec vos parents. Il n'est donc pas nécessaire de construire une nouvelle maison. Mon rêve d'avoir une maison s'est évanoui.

A partir de ce moment-là, nous devions appeler le chef du village 'Baba' (père) ou 'Asa' (chef du village) dans la langue locale Songola, au lieu de 'Sultani' (chef du village) en Swahili. On m'a également appris que mon frère aîné était le "père aîné" et mon frère cadet le "père cadet" et que si, par exemple, il n'y avait qu'une chaise disponible, je devais naturellement la donner à mon père. Le plus jeune père que l'on m'ait présenté était un garçon d'environ six ans à l'époque.

Quelque temps après que je sois devenu le fils du chef du village, une grande réunion de la congrégation protestante voisine devait se tenir dans un village voisin, et lorsque nous sommes arrivés après trois heures de marche, mon père était parmi les nombreuses personnes qui nous ont accueillis et qui ont crié "Fils" ! Je n'ai pas eu le choix. J'ai couru vers mon père en criant "Papa" et je l'ai serré dans mes bras. C'était une performance pour faire savoir au chef du village, qui n'avait jamais eu de fils, qu'il en avait enfin un.

Pour commencer notre travail sur le terrain, nous avons décidé de dresser une carte du village. Takako, qui avait un meilleur sens de l'orientation qu'Eugène, a dessiné la carte. J'ai entendu les villageois murmurer : "Wow, cette femme travaille avec sa tête". L'impression que les villageois avaient de moi a été confirmée par le fait que j'ai préparé des spécimens de plantes pour étudier la relation entre la forêt et les gens. Pendant que Takako ramassait et peignait des plantes, je continuais à fabriquer des spécimens séchés tout en alimentant le feu de bois. Lorsque je me suis rendue dans une maison pour un entretien, on m'a dit : "Ton travail consiste à sécher les feuilles, n'est-ce pas ? Laissez les choses difficiles à votre femme". Néanmoins, j'ai réussi à interviewer une maison, puis une autre, et lorsque je suis rentré chez moi, j'ai demandé à mon père, comme je l'avais fait pour les autres maisons, combien d'enfants avez-vous ? Combien d'enfants avez-vous ? Puis je suis entré dans la maison d'en face d'un homme qui avait sept femmes. Il m'a offert une chaise et m'a servi de l'alcool. Je l'ai bu sans hésiter, car nous avions choisi un village où l'on pouvait boire des boissons fortes. La deuxième femme de mon père est entrée et m'a ordonné d'une voix sévère de rentrer immédiatement à la maison car mon père me réclamait. Je me suis dépêché de rentrer et mon père m'a fait un sermon.

Ma famille et la famille d'en face entretiennent des relations importantes et sérieuses, car nous allons tous deux épouser la femme de la famille d'en face. Nous ne devons pas boire d'alcool ensemble. Je savais donc que le village était divisé en deux groupes de parenté.

En anthropologie culturelle, on appelle cela une "relation d'évitement", c'est-à-dire la sagesse de refroidir des relations qui, autrement, seraient facilement rompues. La relation d'évitement la plus rigoureuse est celle qui existe entre un homme et la mère de sa femme. Par exemple, il est considéré comme impoli de se rencontrer dans la rue et, si une telle situation se présente, le mari est censé se cacher respectueusement dans les buissons pour ne pas être vu. De manière moins stricte, dans certaines relations, il est interdit de manger dans la même assiette. En raison des liens de parenté qui existent dans ce village, nous avons décidé que nous n'étions autorisés à nous détendre et à socialiser joyeusement qu'avec la moitié des villageois.

Les pères et les fils étaient autorisés à manger dans la même assiette, mais cela devait toujours être évité. Dans le village, nous vivions selon le principe de la gratuité. Par exemple, j'ai donné quelques cigarettes à mon père, même si je ne fumais pas, pour avoir transporté du bois de chauffage afin de faire sécher des spécimens de plantes pour que je puisse étudier les connaissances forestières. Je donnais parfois des cigarettes à mon père en signe de respect, mais pour la première fois, mon père m'a demandé : "Que fais-tu de tes cigarettes ?

J'ai répondu : "Papa, je fume dans la maison la nuit".

Un jour, après une période de pluie, j'ai trouvé mon père en train de vendre des cigarettes sur une pierre au bord de la route et je lui ai demandé : "Père, quand fumes-tu ?

Père, quand fumes-tu ? "C'était un échange un peu maladroit et évasif.

Son pendant était le terme un peu curieux de "relation de plaisanterie". Depuis l'enfance, les sœurs et les tantes de mon père venaient me voir à tour de rôle et me suppliaient de leur acheter de l'alcool ou des cigarettes à priser. Lorsque j'ai interrogé les épouses de mon père à ce sujet, elles m'ont répondu qu'elles étaient ses sœurs et qu'elles et moi étions libres de nous demander n'importe quoi les unes aux autres et de plaisanter librement sur des sujets sexuels. Il en va de même entre grands-pères et petits-enfants. C'est pourquoi les traditions orales peuvent s'étendre sur plusieurs générations. Le petit-fils peut savoir quelque chose que son père ignore.

Dans ce réseau d'évitement et de plaisanterie, beaucoup de choses peuvent se produire. Une tante m'a demandé d'aller dans la chambre de son fils pour prendre de ses nouvelles, car il semblait malade. Elle ne pouvait pas entrer dans la chambre de son fils, mais moi je pouvais.

Pendant ce long séjour, la nourriture fournie par la maison de mon père est devenue de plus en plus rare. Je mangeais souvent chez mon grand-père car j'avais de bonnes relations avec lui, qui habitait juste en face, il était donc facile de mendier quoi que ce soit et il m'offrait toujours un repas. C'est au cours de l'une de ces périodes que mon père s'est approché de moi.

Je pensais que tu ne mangeais pas beaucoup à la maison ces derniers temps, mais j'ai entendu dire que tu le faisais chez mon père. Pourquoi ?" Je ne savais pas quoi répondre, alors j'ai répondu honnêtement : "Parce que ni mon père ni ma grand-mère (sa femme plus âgée) ne mangent souvent à la maison."

Mais cela a été interprété comme une accusation contre le tribunal du village, qui se réunit tous les dimanches. Au fil du temps, je suis devenu le plaignant et mon ex-femme l'accusée. Sur la place du village, entouré des villageois, on répétait les arguments, les discours, les témoignages, les proverbes et les chansons. Sous mes yeux ébahis, les anciens ont délibéré et rendu leur verdict. Moi, le plaignant, j'ai gagné le procès.

Immédiatement après le verdict, les femmes autour de moi ont versé du sable sur ma tête. Avant que je m'en rende compte, elles avaient du sable dans les mains. Elles m'ont dit. Ne sois pas arrogant parce que tu as gagné". Je me suis souvenu qu'un homme qui avait gagné un petit procès s'était fait verser du sable par les femmes qui l'avaient recueilli. Plus tard, lorsque mon père a donné naissance à sa première fille (ma sœur) le jour même de mon arrivée au village, on lui a également jeté du sable et il a dit : "Si c'était un garçon, tu aurais eu une tempête de sable plus forte, félicitations ! Ils ont dit : "Si c'était un garçon, tu aurais eu une tempête de sable plus forte, félicitations !

Après les six premiers mois, le jour où j'ai quitté le village pour rentrer chez moi, j'ai remis mes affaires aux personnes qui s'étaient occupées de moi. Peu après, j'ai été appelé dans la chambre de mon père et j'ai été réprimandé.

Tu as donné cette machette à mon père. Je la voulais pour moi. Papa, je te l'ai donnée parce que mon grand-père me l'a demandée. Si tu la voulais tant, tu aurais dû me le dire.

Comment un père peut-il demander à son fils de lui donner quelque chose ? C'est très malheureux".

Le fils aurait dû donner des choses à son père pour que celui-ci ne lui dise pas ce qu'il voulait. En particulier, il aurait dû éviter de faire des cadeaux en public. En effet, les yeux de ceux qui ne recevaient pas de cadeaux étaient jaloux et portaient malheur. En swahili congolais, le mot pour jalousie est kiricho, qui signifie aussi "grands yeux".

La paternité.

Lorsque nous adoptons un enfant, nous ne pouvons pas mettre fin à la relation.

Nous ne pouvions mener nos recherches que dans le cadre d'une série de relations définies : il était difficile de collecter du bois de chauffage pour plus de 1 000 spécimens de plantes et, pendant notre séjour, nous devions demander à la femme de dos de mon père, qui avait mal au pied, d'aller chercher de l'eau pour nous tous les jours. Nous avons donc décidé d'engager un garçon comme assistant. Cependant, lorsque les deux mères ont vu le garçon, elles ont dit à l'unisson : "Si vous avez besoin d'un garçon, pensez à un autre garçon. Si vous avez besoin d'un garçon, considérez-nous comme votre fils et demandez-nous tout. C'est ce qu'elles ont dit, et nous sommes retournés à nos anciennes habitudes.

Un jeune homme est venu au village pendant son temps libre, a marché avec nous pendant deux heures jusqu'au village voisin et a visité le magasin. Mon fils, ne sors pas avec ce jeune homme. Les pères de ce jeune homme sont tous morts et il est orphelin. Je suis désolé pour lui, mais il doit savoir qu'il est libre de toutes les contraintes du monde quant à la manière dont il doit se comporter devant son père.

Vous n'êtes pas orphelin, alors ne faites pas l'erreur d'imiter son comportement".

Ayant un "père junior" d'une vingtaine d'années plus jeune que moi, j'ai peut-être eu la chance d'entrer dans une "vie sans père". Aussi, lorsque j'ai dit aux villageois que je n'avais eu qu'un père et une mère au Japon, ils ont été très choqués. Je ne peux pas vivre dans un endroit aussi froid et solitaire". De leur point de vue, notre lien de parenté avec un seul père et une seule mère était très étrange. J'ai appris les systèmes agricoles des villages forestiers, les noms des poissons dans les villages de pêcheurs riverains et l'économie de troc qui relie les différents milieux de vie. Takako a étudié la cuisine, la brasserie et la relation avec le monde végétal. Son père lui a dit : "Il y a un village au bord de la rivière. Il y a un village au bord de la rivière où ta sœur, la fille de ton frère, est mariée au chef du village, alors tu peux y rester.

Pour le chef de ce village au bord de la rivière, j'étais un parent qui avait cédé sa femme en échange de 10 chèvres en guise de cadeau de mariage. Ma relation avec le chef du village était plus formelle que celle d'un père et d'un fils.

Un jour, après les pluies, j'ai glissé sur le sol mouillé dans la cour de la maison du mari de ma sœur où je logeais et j'ai failli tomber juste devant lui. Les villageois m'ont regardé et m'ont dit : "Dommage, tu as raté la chèvre !

Si j'avais glissé, le mari de ma sœur m'aurait aidée à me relever et m'aurait donné la chèvre pour me dédommager de la honte d'être tombée devant lui et tout le village aurait pu la manger. De même, mon père et moi avions une relation abominable : nous n'avions pas le droit de nous dire "donne-moi des choses", mais nous pouvions manger dans la même assiette et nous pouvions manger le poulet ensemble. Le mari de ma sœur et moi n'avions pas le droit de manger dans la même assiette. Le poulet était apporté à la table dans un pot contenant toutes les parties du poulet, et les invités étaient libres de choisir ce qu'ils voulaient manger, qui était ensuite partagé avec le reste de la famille. Les poulets avaient des parties savoureuses, comme le cœur et le foie, qui étaient trop petites pour être partagées, ce qui évitait les disputes embarrassantes qui pouvaient compliquer les relations importantes mais délicates entre les membres de la famille en raison du mariage.

Lorsque j'ai fait des recherches sur le savoir populaire concernant le poisson (Ankei Yuji, 1982), j'ai également interrogé le mari de ma sœur. Lorsque je lui ai demandé le nom du trou où l'on trouvait des excréments de poisson, il a été embarrassé et s'est tu. Oh non ! De telles questions sont acceptables entre des personnes qui plaisantent, mais ne devraient pas être posées entre des personnes qui s'évitent. De même, lorsqu'un père lui a parlé de plus de 500 plantes de la forêt, elle lui a demandé le nom d'une plante, mais il n'a pas répondu, disant qu'il était gêné. Plus tard, lorsque Takako a interrogé les mères, elles lui ont dit qu'il s'agissait d'une plante utilisée à des fins sexuelles (Ankei Takako, 2009). Le fait d'être impliqué dans de tels liens de parenté sur le terrain avait deux aspects : l'un était que la recherche se déroulait sans problème, et l'autre était qu'elle était étonnamment contraignante.

Ma troisième visite au Congo a eu lieu en 1983. Mon fils venait de naître et Takako était au Japon avec le bébé. Lorsque je suis arrivé au village, j'ai tout de suite dit à mon père : "Père, un petit-fils vient de naître. Père, un petit-fils est né". Je me suis rendu compte que j'avais fait une terrible erreur. Quand j'ai demandé à mon père comment s'appelait le bébé, il a été déçu et m'a donné trois noms. Ni Ngoli (homme libre), ni Musafiri (voyageur), ni Ruapanya (héros mythique). ......"

C'est à ce moment-là que l'aide céleste est descendue.

"Je lui ai donné ton momamba (nom linguistique du tambour) bobobobo bobobo (ruapanya bungu kunguwa) !"

En entendant cela, la réaction de mon père, un grand sourire aux lèvres, fut étonnante." Il m'a enfin mis au monde !" À partir de ce jour, mon nom a été changé dans le village et on m'a appelé "le père de Ngoli".

Les mères ont également commencé à dire "ton fils m'appelle" au lieu de "ton père m'appelle". En d'autres termes, ceux qui partagent le même nom sont la même personne, et tant que la personne qui partage le nom est en vie, elle a une vie immortelle, même si son corps périt.

Vivre le mythe

Lors de ma deuxième visite, j'ai pris conscience que la langue songola possède un long mythe de héros. L'homme d'une trentaine d'années qui m'a raconté le mythe était un conteur habile et dramatique, qui égrenait une série de chants magiques apportant miracles et merveilles dans les aventures herculéennes de Kamangu, un héros culturel miraculeusement né sous la forme d'un frère chimpanzé. J'ai exploré le monde souterrain jusqu'au pays du tonnerre. Le soir, alors que je chantais avec le public au coin du feu, j'ai eu l'impression que les anciens mythes japonais, tels que le Kojiki, étaient racontés comme une pièce de théâtre et que le public chantait des parties des chansons de cette manière. J'ai planifié un voyage de 100 km jusqu'à un village au fin fond de la forêt où cette tradition serait encore vivante et j'en ai discuté avec mon père.

Mon père m'a répondu qu'il pouvait aussi me raconter cela. Mais le mythe que mon père m'a raconté était différent du mythe

"Papa, pourquoi ne m'as-tu jamais dit que ce mythe existait ?" Je lui ai demandé : "Pourquoi ne m'as-tu jamais demandé ? Mon père m'a répondu : "Il ne m'a pas dit le nom du dieu enragé, mais un juge du tribunal qui se trouvait par hasard dans le village, à ma demande, l'a écrit dans son carnet et me l'a lu. Le mythe était presque identique à celui que mon père m'avait raconté, sauf que les répétitions étaient supprimées et les chants raccourcis. La seule différence était qu'il nous avait dit que le nom du dieu enragé était Luapanya. C'est à ce moment-là que j'ai réalisé que le récit d'une aventure au pays des sangliers, que j'avais entendu plusieurs fois dans les brumes nocturnes de mon précédent séjour, était un fragment de ce mythe héroïque, et je me suis soudain souvenu que seul mon père l'avait raconté à la première personne.

Le héros de cette partie de l'histoire était Luapanya, mon père du même nom a donc raconté le mythe à la première personne comme sa propre aventure. Les actes héroïques du mythe de Luapanya étaient les siens et ceux de mon fils, qui portait également le nom de Luapanya. J'avais senti se dissoudre en moi un certain malaise face à la tradition orale du peuple Ainu, racontée à la première personne par une divinité non humaine, Kamui.

Les mythes du peuple Songola, qui sont encore racontés de façon vivante aujourd'hui, ne parlent pas d'un passé lointain, mais sont directement liés à la façon dont nous vivons aujourd'hui, et il n'y a pas eu qu'une seule version des mythes autorisée et écrite, ni que seule la famille du roi ait eu le privilège d'être affiliée aux héros des mythes. Ces mythes sont les rêves des habitants du pays, qu'ils ont conservés malgré les grandes difficultés de la colonisation et les guerres civiles répétées. La rédaction des mythes a été un véritable défi pour la langue songola, une langue minoritaire pour laquelle il n'existait ni dictionnaire ni grammaire, et pour la culture songola, inconnue, pour laquelle notre seule recherche antérieure était une ethnographie publiée par un administrateur colonial en 1909.

Le souhait d'un oiseau migrateur

En 1990, je suis retourné dans les forêts de la République démocratique du Congo, où vivait mon père, pour la première fois depuis sept ans. C'était mon quatrième voyage. Après avoir débarqué de l'avion et être entré dans l'hôtel, j'ai immédiatement écrit une lettre pour le village où vivait ma sœur. Un batelier sur une pirogue descendant le fleuve a accepté de porter cette lettre. Cependant, des rumeurs circulaient qu'un meurtre avait eu lieu dans le village et que la population avait été dispersée par des vengeurs et des pillages par des soldats qui prenaient le nom d'interrogatoire, laissant le village presque à l'abandon.

Le village de ma sœur était un village qui croyait à l'islam en 1980, mais qui s'est un jour converti au catholicisme et, en 1983, les hommes buvaient de l'alcool distillé en plus du vin de palme auquel ils étaient habitués. Comme cette liqueur était fabriquée par les femmes, un canal a été créé pour transférer les revenus des hommes vers les femmes, mais je craignais que ce changement ne comporte certains pièges dangereux. J'avais l'intuition que la cause de l'abandon des villages était peut-être la consommation d'alcool.

J'ai donc décidé de m'abstenir presque complètement de boire de l'alcool. La première chose que j'ai faite a été de conseiller au chef du village, le mari de ma sœur, d'arrêter de boire ou au moins de réduire sa consommation d'alcool. Lorsque je suis arrivée dans le village, j'ai découvert que le meurtre avait été commis à la suite d'une dispute au sujet de l'alcool. Les gens reprenaient peu à peu leur vie normale, mais certaines femmes se noyaient dans l'alcool.

Lorsque j'ai parlé au chef du village, le mari de ma sœur, j'ai constaté qu'il était quelque peu déprimé et qu'il estimait que l'endroit où il mourrait n'avait pas d'importance. M. Bernard, le mari de la sœur du chef, était très inquiet que si le village disparaissait, les immigrants pourraient s'approprier toute la forêt à l'est du fleuve Lualaba. Il m'a donc demandé si je pouvais, d'une manière ou d'une autre, encourager le chef de village à l'aider à faire revivre le village.

L'année précédente, nous avions franchi la limite en tant que chercheurs en créant une entreprise de production et de vente de riz sans pesticides sur l'île d'Iriomote, à Okinawa (Miyamoto & Ankei, 2008). Cette fois, j'ai décidé de lancer un projet de revitalisation du village avec le conseiller du chef, M. Bernard. Bien sûr, les manuels d'anthropologie nous disent qu'il est correct pour les travailleurs sur le terrain d'enregistrer objectivement de tels incidents et changements sociaux. Cependant, M. Bernard était le pilote qui m'avait guidé lors d'un voyage en canoë en bois de 250 km sur le fleuve Lualaba sept ans plus tôt, en 1983, et il m'avait sauvé la vie au cours de ce voyage ardu. Et c'est le village de ma sœur qui est sur le point d'être abandonné.

J'ai parlé au chef du village de l'importance de s'abstenir de boire plutôt que d'apprécier l'alcool, et du fait qu'il ne pouvait pas persuader les gens d'arrêter de boire s'il buvait lui-même. J'ai mentionné que notre dieu Kamangú, dans le mythe de Songola, avait brisé un tabou en s'enivrant. Je lui ai également dit que si le village devait être abandonné pendant son règne, dans le cas improbable où nous serions privés de nos droits sur cette forêt, l'histoire serait transmise aux générations suivantes, en disant : "Cela s'est passé à la génération de ce chef". Après cette conversation persuasive, je pouvais l'entendre dire : "Nous parviendrons à réessayer."

Ensuite, il s'agissait de faire sortir les personnes emprisonnées, de payer les amendes pour les armes confisquées, de faire des radios et de soigner le chef du village lui-même, qui avait une toux qui ne s'arrêtait pas. Je n'avais jamais donné d'argent dans de telles situations auparavant, mais maintenant que j'avais pris la parole, j'ai également décidé de donner l'argent nécessaire au rétablissement du village. J'ai donc suivi le modèle de comportement de Wildcat-Brand Iriomote Island's Organic Rice à Okinawa.

Je suis allé plus loin dans le village de mon père, dans la forêt. Mon père, que je n'avais pas vu depuis longtemps, était aveugle d'un œil à cause d'une maladie et avait l'air vieux et faible. Il se demandait pourquoi je n'étais pas venu le voir pendant sept ans. "Chaque fois que je voyais la lune dans le ciel, je ne pouvais m'empêcher de penser à toi. Viens, mangeons dans la même assiette", disait-il. Cependant, mon village était en proie à une grande agitation. Je n'ai pas le droit de vous parler de nos problèmes familiaux, mais l'un de mes jeunes frères faisait du tapage tous les jours, criant et hurlant qu'il allait porter son affaire devant le tribunal de la ville. Mon père comptait le plus sur lui, et il semblait certain qu'il hériterait du poste de chef de village de mon père à la génération suivante. Tout a commencé lorsque son père lui a caché sa compagne qui se disputait avec lui. La règle inflexible du chef de village en tant que refuge était que "ceux qui s'échappent entre les mains du chef de village ne meurent jamais".

Le jeune frère, furieux, a poursuivi son père devant le tribunal de la ville. En conséquence, le père a été emprisonné et a dû renoncer à son argent et à ses chèvres pour être libéré. Le père a déclaré qu'il ne pouvait pas permettre à un imbécile d'occuper le poste de chef de village, qui perdrait les biens qui lui reviennent normalement sous la forme de la richesse des mariées pour ses propres mariages. Mon père a donc nommé chef de village adjoint un ancien esclave qui avait été privé de la connaissance de ses racines et de sa langue maternelle. Le frère cadet, furieux de ce choix, a tenté de poursuivre le chef adjoint en justice. Le village de ma sœur était presque abandonné, et mon propre village était dans une telle tourmente. Si rien n'est fait, même mon propre village pourrait être abandonné. ...... J'étais tellement inquiet que j'ai appelé mon jeune frère pour lui parler. Je lui ai demandé : "Sais-tu pourquoi mon père a insisté pour qu'un ancien esclave prenne la tête du village ? Je lui ai demandé. "Parce que, bien que je sois désolé pour lui, personne ne croirait que son choix est sérieux. En Songola, il y a un dicton dans notre mythologie qui nous enseigne que "mo.kota tá.móne tá.kui" (un chef de village ne voit ni n'entend), c'est-à-dire qu'il faut rester calme et ne pas se laisser distraire par des choses insignifiantes. Vous avez été chef adjoint d'un village, ne savez-vous pas que plus vous vous préoccupez de chaque petite chose comme d'un procès, plus votre père sera dégoûté de vous ? Le poste de chef de village est comme un palmier à huile qui pousse en abondance dans ce village. Si vous restez tranquilles, la graine tombera sous l'arbre et y repoussera. Si nous créons une tempête, les graines s'envoleront et pousseront loin du tronc". Après avoir parlé pendant un moment, il dit : "Je comprends maintenant, mon frère. Je suis désolé. Je m'excuserai auprès de notre père."

Le lendemain, mon frère aîné (le fils du frère de mon père), en qui Takako et moi avions le plus confiance, est venu nous voir à pied depuis une ville située à une trentaine de kilomètres. Ce soir-là, alors que je discutais avec mon frère aîné et mon père, j'ai eu l'idée de leur raconter cette histoire impromptue en swahili. Il pleuvait dehors et les épouses restées à l'intérieur ne pouvaient pas écouter.

Je leur ai raconté une histoire : "Il était une fois une forêt de palmiers à huile comme ce village. Il y avait un grand palmier dans la forêt, et les oiseaux venaient même de loin pour y faire leur nid. Un jour, cependant, les feuilles et les racines du palmier ont eu un conflit. Les feuilles voulaient éviter de faire de l'ombre aux racines, et les racines voulaient éviter d'envoyer de l'eau aux feuilles. Pendant ce temps, le tronc commençait à se dessécher et à pourrir. Une nuit, il y eut une tempête et le puissant palmier à huile se brisa soudainement en son milieu. Alors, la prochaine fois qu'un oiseau migrateur se présentera, où diable devrait-il nicher ?"

"Ce n'est pas une vieille histoire. Il s'agit d'un appel au tribunal", a marmonné mon père, et les deux auditoires se sont tus. Je craignais d'avoir fait une erreur. C'était peut-être quelque chose qu'un fils ne devrait jamais dire à son père. Je me suis retiré dans ma chambre sans même dire bonjour.

Le lendemain matin, mon frère aîné est venu me voir. Il m'a dit : "J'ai été très impressionné par ton histoire d'hier soir. Notre père vous est reconnaissant et cite le proverbe : "Un fils qui vient de loin a de la piété filiale". Vous êtes la personne même de ce village. Votre corps est peut-être né dans le lointain Japon, mais vous êtes originaire de ce village. Votre parabole était comme une lance acérée pénétrant dans nos cœurs, et ni mon père ni moi n'avions un mot à répondre. Nous réunirons toute notre famille la prochaine fois, alors s'il vous plaît, faites-leur entendre à nouveau cette parabole. ......

Plus de 20 ans se sont écoulés depuis lors sans que je puisse me tenir debout dans mon village natal. Maintenant que j'ai envoyé mes parents au Japon, j'ai envie de retrouver la chaleur et la nostalgie d'une grande famille africaine. Pendant mon séjour au Kenya en 1998, ma famille et moi avons essayé de visiter le village où mon père et sa famille nous attendaient, mais nous avons dû abandonner l'idée deux jours avant notre départ de Nairobi en raison de l'éclatement de la guerre civile. Depuis lors, nous avons passé nos journées à visiter des pays dotés de forêts, tels que le Kenya, l'Ouganda et le Gabon en Afrique de l'Ouest, en espérant que la paix reviendra aux habitants des forêts de ma seconde patrie.